HMI (Human Machine Interface) is the link between machines and their humans. It is often seen as a very modern thing that is only relevant to the computer age, but machines have been around for a long time and have always needed control and feedback mechanisms at the command of humans.

We have used simple tools—cutting tools, the wedge, the inclined plane, the axe—since prehistoric times, but the first real machines, with compound parts and more complex uses, are thought to have been created between 5,000 and 7,000 years ago—the wheel, the axle, and the lever. Even these simple machines have an HMI, as they are used by humans. So, the history of HMI is long, and the lessons learned from early machines have been built on for the vastly more complex machines we use today. Due to the history and complexity of this subject, I will be writing more than one blog post on HMI. Stay tuned for Part 2.

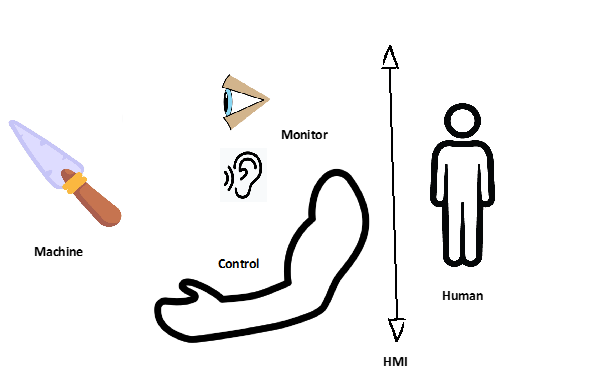

Looking back to simple tools, I believe that the HMI aspects of these are generally overlooked. Just about all definitions of HMI refer to modern control systems with hardware and software elements used to control and monitor their operation, but consider the problems our prehistoric ancestors would encounter if, for example, cutting tools were not used correctly. This is a very simple case, but as with many simple cases, it highlights some very important factors. A cutting tool based on chips broken off a flint stone are sharp-edged pieces, making them useful for knife blades. This gives it a purpose, to cut or scrape, an operator, someone who wants to cut material or scrape off one material from another, an operational method, how to hold/use the tool to perform its operation, and a monitoring requirement, has the cut/scrape operation produced the required results. This all assumes the tool has been correctly designed and is fit for its intended purpose. The human and the interface, in this case, are one and the same. There is no separate control and monitoring system between the human and the machine. However, it can be imagined that part of the human’s mind and body are actually the HMI here.

Human Using Flint Knife

The human wants to cut an animal skin to use for making clothing and uses a knife (the machine) to perform the cutting. They control it with their hands and arms, and monitor it with their eyes, ears, and via touch. The human is at one with the whole process. There is nothing that is not directly under human control. The only “software” is the brain.

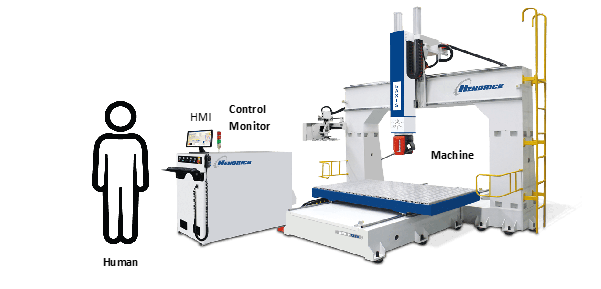

In the modern world we have a human using a Computer Numerical Controlled (CNC) Router. In this example, a human (via the machine, of course) cuts out stuff from big sheets of metal. The metal is too heavy to “man handle”, so the machine cuts, moves, and supports it. The cutting is too accurate to be performed manually, so the machine does that too. It’s difficult for the human to “see” what’s happening, so the control/monitor system does that as well. However, it’s essentially the same as the flint knife setup, except for being able to move the human and their control/monitor system to a location remote from the machine itself. Whether it’s local or remote to the human makes no difference because their HMI is what they use do the work, not the machine directly.

Human using a Hendrick HHD-V Series 5 Axis CNC Router

The historical advances in the functions and complexity of machines gave rise to much more reliance on control/monitor systems, to drive the machine under the ultimate control of a human operator. That makes the HMI all the more important, too. When the human cannot possibly interact directly with the machine, the HMI must do that task and must also present information about the machine’s operation back to the human, who can in turn control what the machine does, all through the HMI.

From simple flint knives to CNC machines, the HMI is a very important component. Whether it is implied and mostly in the human mind and body or a separate system in its own right, HMI design and implementation can make or break machine control.

Come back for Part Two, as I continue to explore this fascinating topic.